Unboxing the NVIDIA DGX Spark: First Impressions

Unboxing the NVIDIA DGX Spark, hardware and software components, benchmarks, target audience and clearing a few misconceptions.

Welcome to The AI Merge. Each week, I write about practical, production-ready AI/ML Engineering. Join over 7000+ engineers and learn to build real-world AI Systems.

I’ve always leaned towards NVIDIA hardware. It started years ago when I was adding parts to my wishlist for building my dream gaming PC, and it continued as my work shifted toward AI development. Over time, a large majority of the GPUs and edge devices I’ve built on or deployed AI on have been NVIDIA-based because that’s where the ecosystem, tooling, and performance consistently came together.

I’ve worked on Jetson Nano, Jetson AGX Xavier at the edge, RTX 3090, 4090, L40, A2, and more in workstations, and datacenter GPUs A100, or H100. While each serves a different role, some prioritizing memory capacity, others raw compute or newer CUDA capabilities - they all reflect NVIDIA’s focus on end-to-end acceleration across hardware and software.

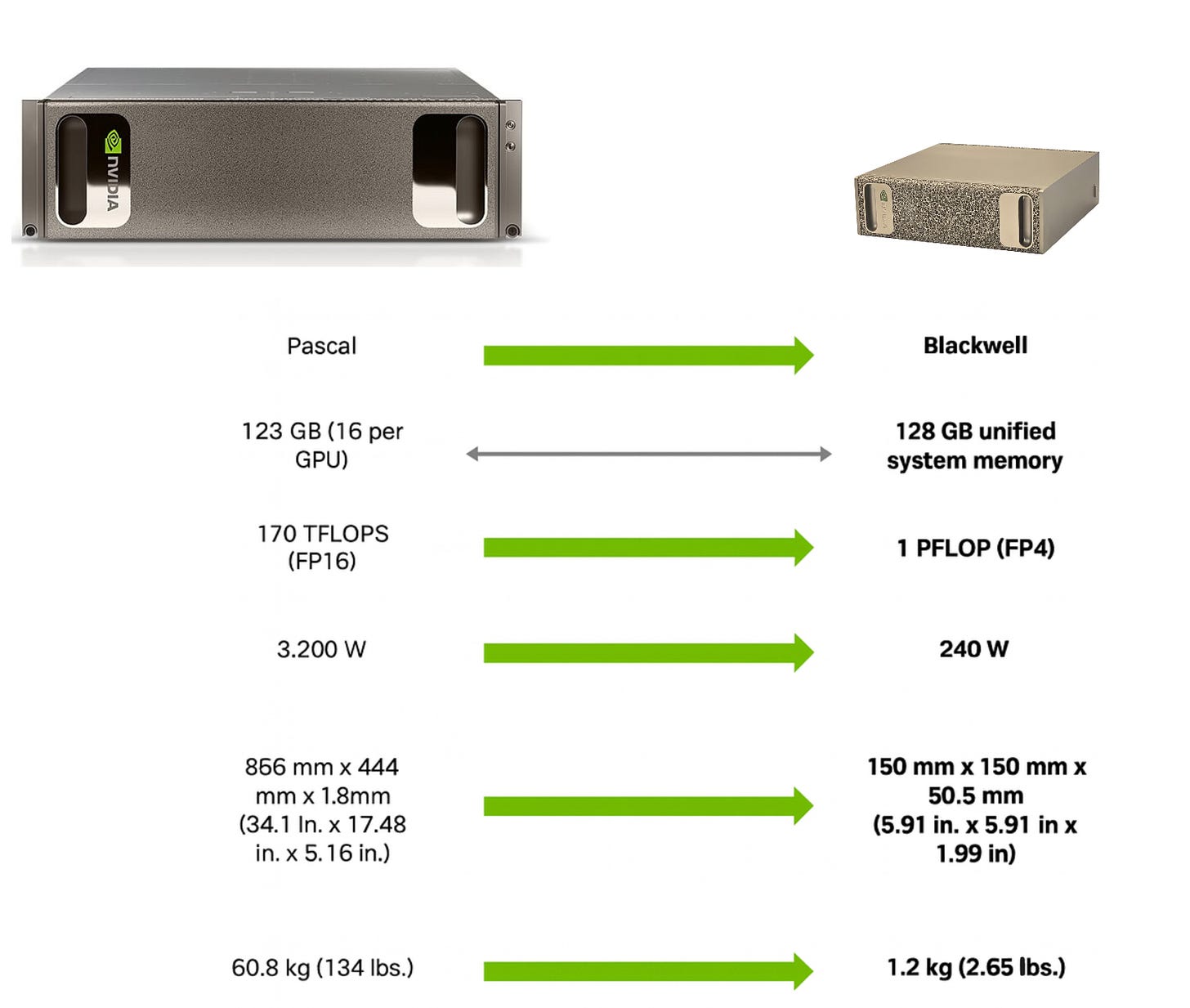

With DGX Spark, NVIDIA is targeting a sweet spot in local AI development: a desk-side developer kit with large unified memory, power-efficient design, and a capable GPU, built for AI engineers to develop, test, and validate models locally before scaling out to the cloud or large clusters.

Past development, modern AI ultimately scales to massive (mostly) NVIDIA-powered superclusters.

Note: AI Superclusters tend to go with NVIDIA GPUs, xAI’s Collosus Supercluster, Microsoft + OpenAI, Nscale + Microsoft and the *potential Stargate Project.

In this article, I’ll take a hands-on look at the system, starting with the unboxing and hardware design, then moving through the software stack, intended audience, and a few benchmarks.

Starting with a few Notes

Lately, many early comparisons have evaluated DGX Spark against multi-GPU workstation builds - configurations like 4× RTX 4090, 2× RTX 5090, RTX PRO 6000 Blackwell, or even Apple’s M-series Ultra systems - and concluded that Spark is “underperforming” based purely on raw throughput metrics.

These comparisons assume that DGX Spark is intended to compete as a high-end GPU replacement. It isn’t.

DGX Spark is positioned as a local, DGX-aligned AI development system, not a benchmark-driven workstation. Its goal is to provide a coherent hardware–software environment for building, testing, and validating AI systems locally, using the same architectural assumptions that apply in NVIDIA’s datacenter platforms.

Once that framing is clear, the tradeoffs behind common benchmark comparisons become easier to interpret.

Apples vs Oranges Comparison

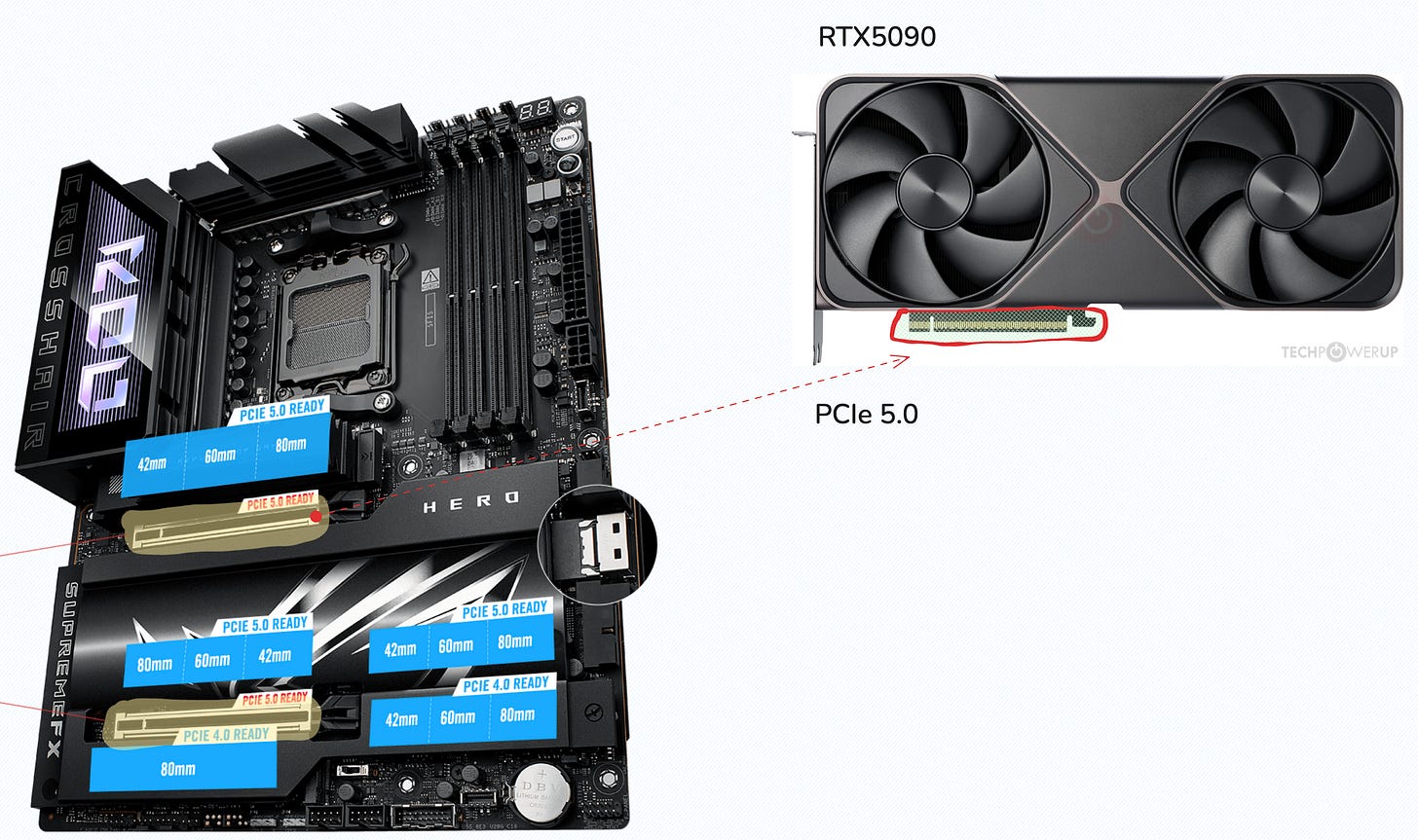

A single RTX 4090 offers strong raw performance with 24GB of GDDR6X VRAM over PCIe 4.0 x16. Scaling to larger memory capacities requires multiple cards, 4x to reach 96GB, introducing fragmented memory pools, PCIe-based interconnects, and more power consumption.

The RTX 5090 has a better bandwidth and capacity (32GB GDDR7 over PCIe 5.0 x16), but you’d still require 4x5090 to get 128GB VRAM, and they’re not cheap either.

On the workstations, the RTX PRO 6000 Blackwell has 96GB of ECC GDDR7 with large memory bandwidth, but it’s an $8,000+ card.

Apple’s M-series Ultra has large unified memory pools and excellent power efficiency, but NVIDIA ecosystem.

The DGX Spark is not a simple GPU; it’s an AI development platform, and I think - a good sweet spot within all the configurations above. It replicates the NVIDIA DGX into a powerful desk-side mini PC, focusing on 4 important pillars:

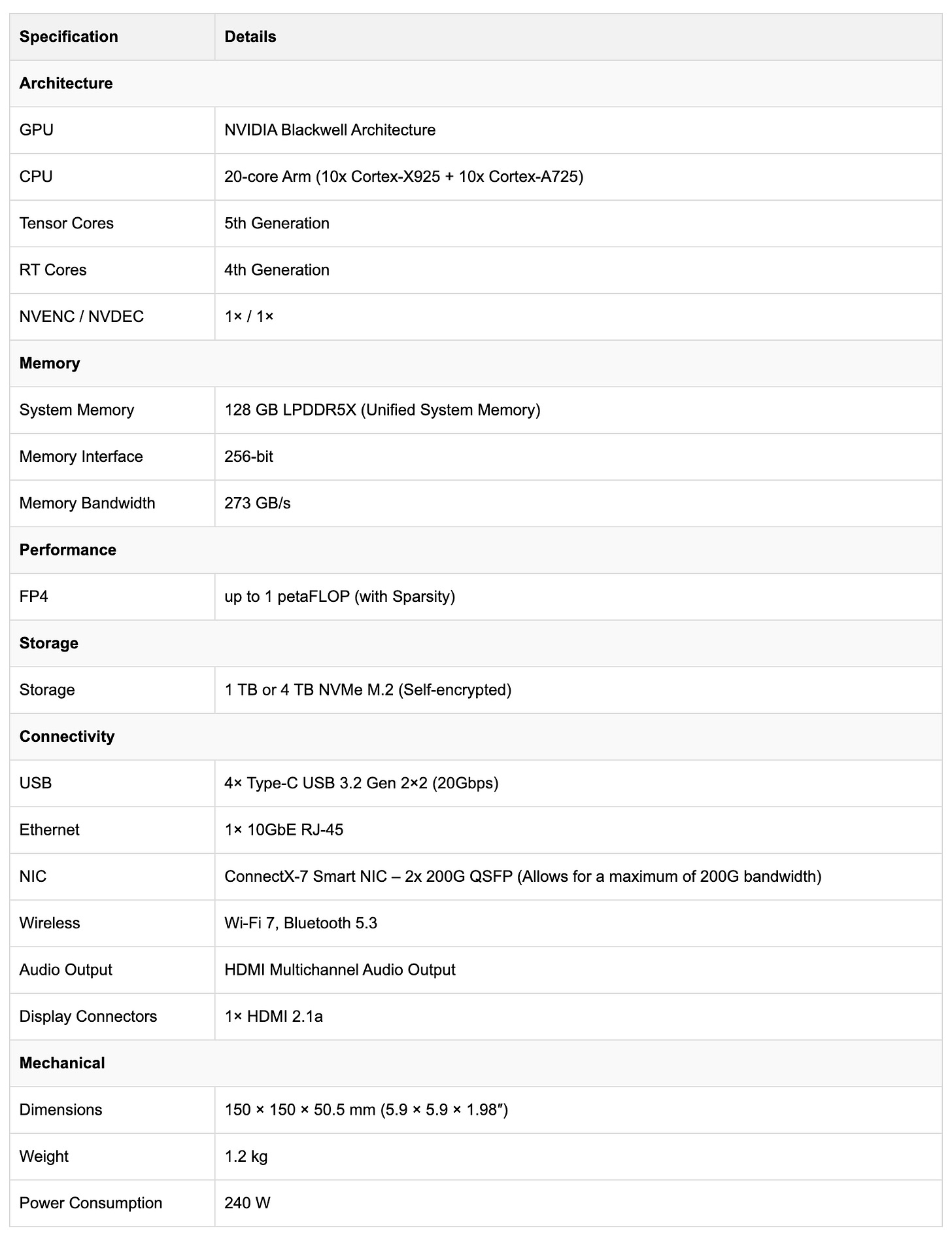

The GB10 Blackwell Chip - with support for FP4 and NVFP4 (up to 1 PFLOP of FP4 performance), which aligns it directly with NVIDIA’s current and future AI compute roadmap.

Large VRAM and Storage - Spark features 128GB LPDDR5x unified memory and supports up to 4TB SSD.

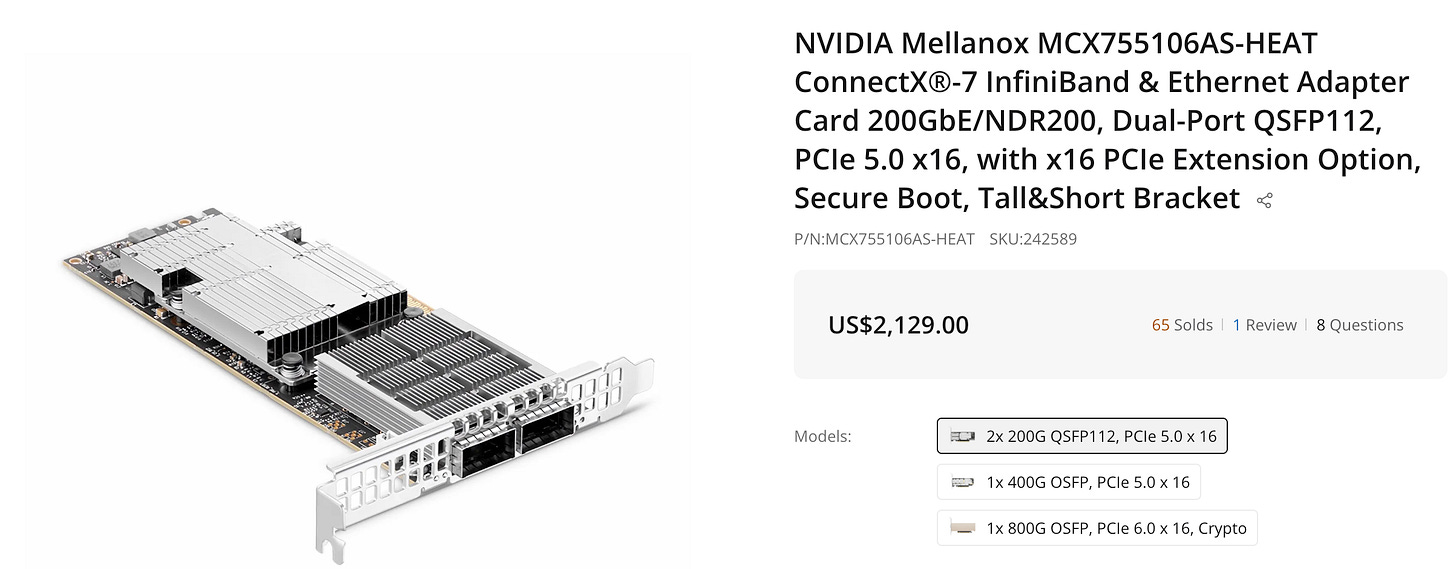

Datacenter Networking - Spark ships with dual QSFP ports powered by a ConnectX-7 NIC, delivering 200 Gbps networking out of the box. The NIC alone is a ~$1,700–2,000 component, something you simply don’t get in standard workstations or consumer desktops.

NVIDIA AI Software Stack - Spark runs DGX OS, preconfigured with NVIDIA’s full AI software stack, including core AI libraries such as CUDA, NCCL, cuDNN, TensorRT, and the rest.

Judging DGX Spark purely on raw benchmark numbers misses its value proposition. It is not designed to replace multi-GPU workstations, nor to compete on inference performance alone. Instead, it provides a compact, coherent, and datacenter-aligned AI development environment that mirrors how models are ultimately trained, distributed, and deployed at scale within NVIDIA’s ecosystem.

When evaluated on those terms, the design tradeoffs of DGX Spark are deliberate and consistent with its intended role.

Hardware and Design

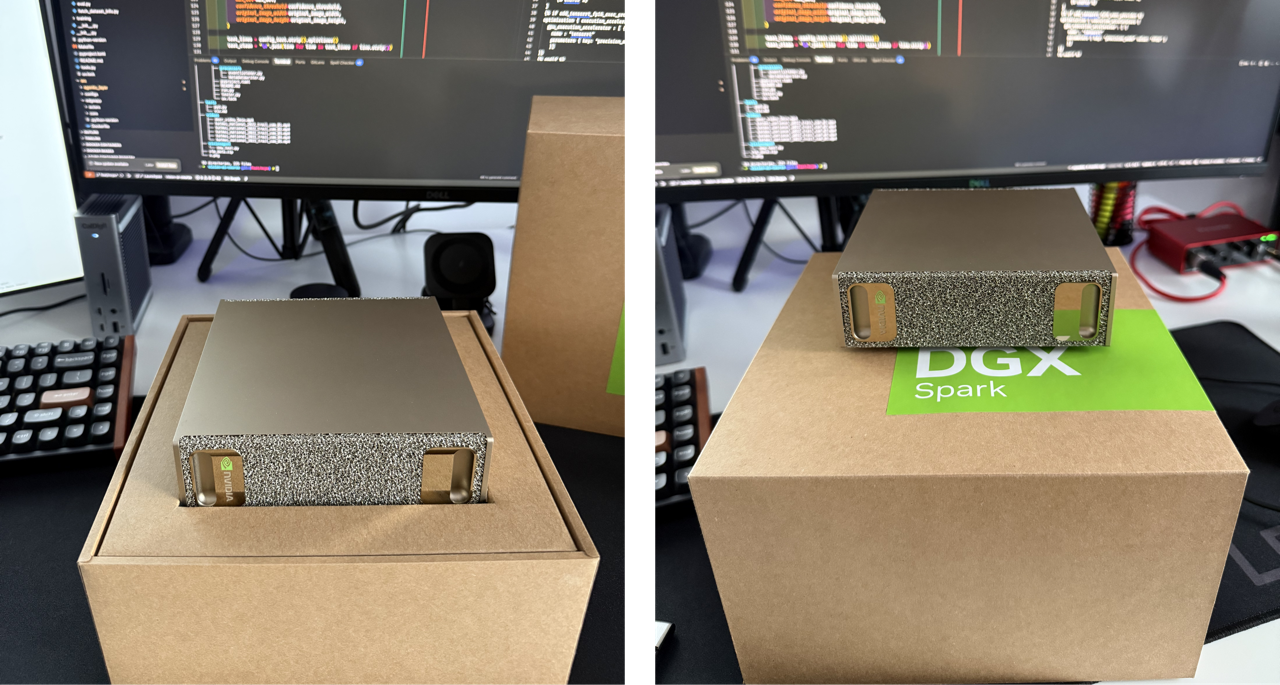

The DGX Spark is a gorgeous piece of engineering. It’s got a full-metal chassis with a gold-like finish, has two metal foam front/back panels which are strikingly similar to the design of NVIDIA DGX A100 and H100.

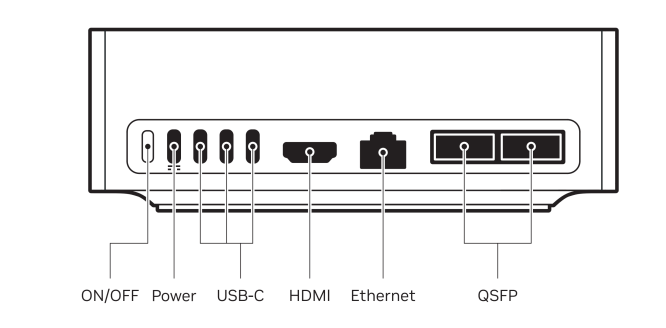

Physically, it’s a small and elegant unit, roughly the footprint of a Mac Mini. On the back panel, it’s got:

4 x USB-C ports, with the leftmost one being the power delivery(up to 240W)

1 x HDMI 2.1a display connector port to plug in your monitor

1 x Ethernet 10 GbE RJ-45 Ethernet port

2 x QSFP ports, driven by NVIDIA ConnectX-7 200GB/s NIC

Note: QSFP (Quad Small Form-factor Pluggable) is a hot-pluggable optical or electrical interface used in high-speed networking equipment such as switches, routers, and servers.

The QSFP ports are particularly interesting, as underneath they’re powered by a premium datacenter ConnectX-7 NIC (Network Interface Controller), allowing you to build a mini-DGX cluster locally with only 2 DGX Spark Units, and working with LLMs over 400B parameters.

The exact NIC model that Spark has comes in the 200GB/s via 2 QSFP ports, split into 100GB/s per port. The example shown in the following image is the 2x200GB/s at USD $2200, placing the Spark version of this NIC at around 60-70% of that price (~USD $1500).

At the datacenter scale, networking is what enables efficient multi-GPU and multi-node parallelisation through NCCL. With ConnectX-7, multiple DGX Spark units can be directly connected or attached to a high-end switch, and as ConnectX-7 supports RDMA and GPUDirect RDMA, Spark can also move data directly from storage or edge systems into GPU memory with minimal CPU involvement, something traditional workstations simply aren’t designed to do.

For local and edge AI, this matters when working with large datasets, streaming data, or building systems that more closely resemble production AI infrastructure.

Hardware Specifications

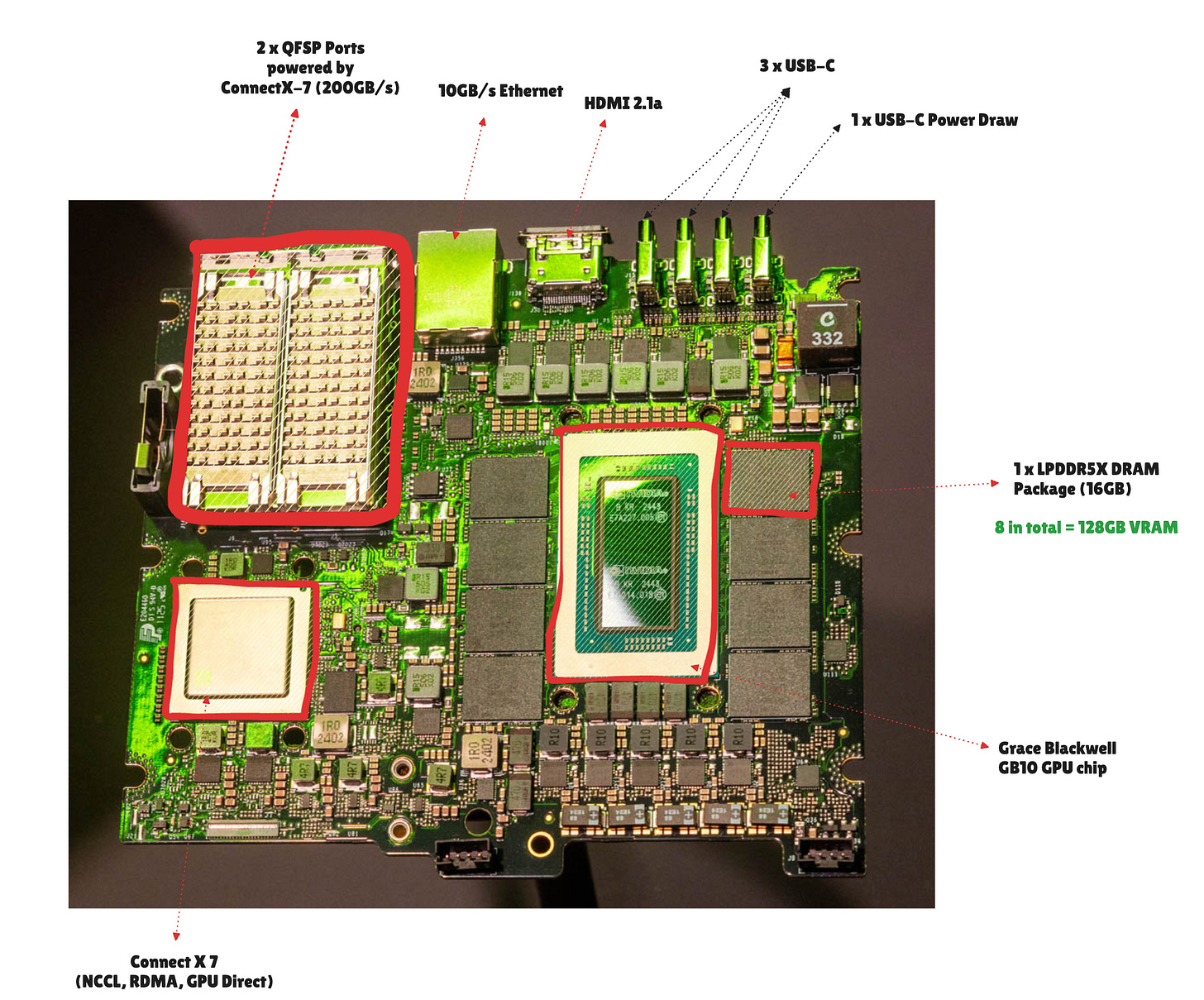

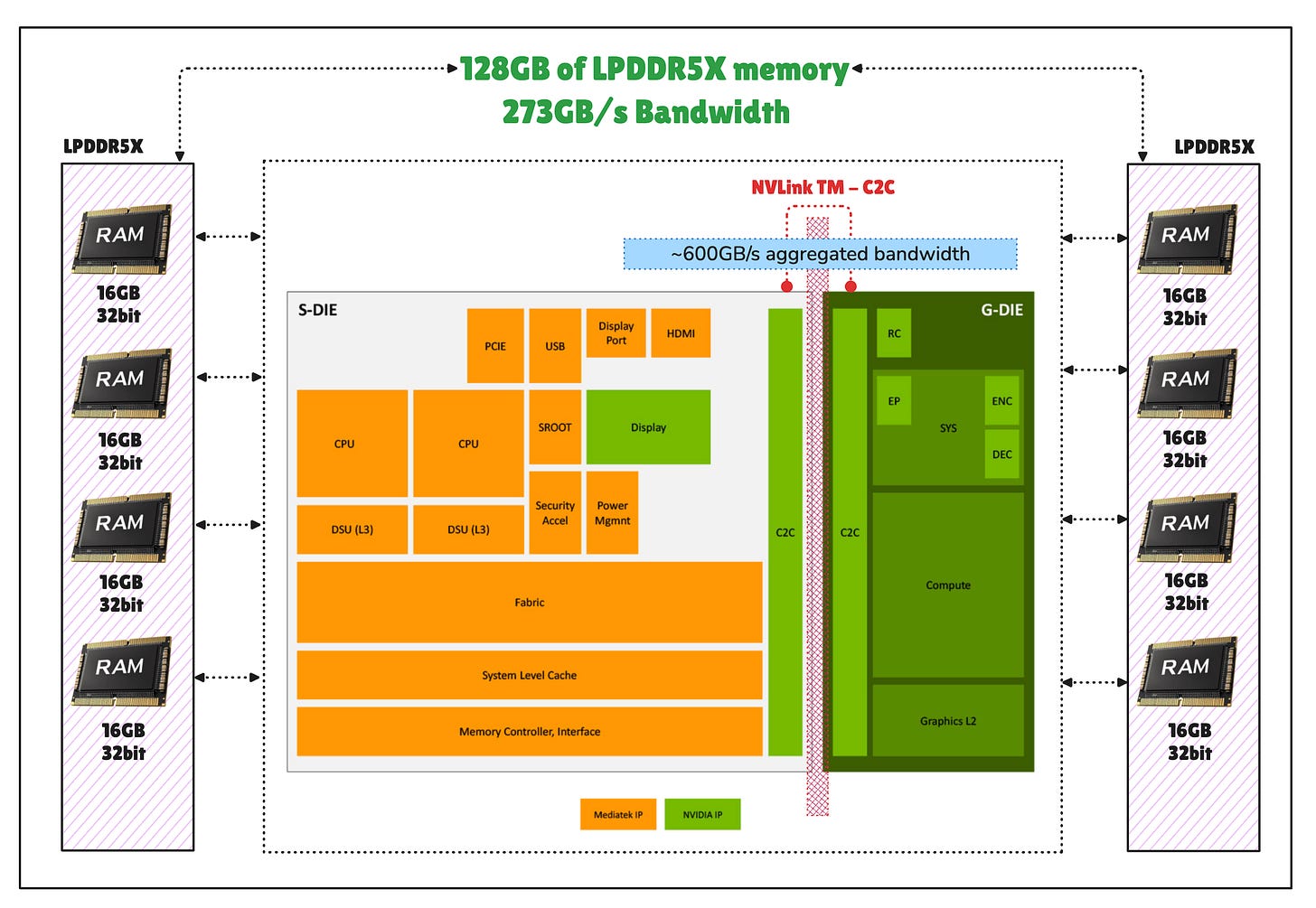

The DGX Spark is powered by the GB10 Grace Blackwell Superchip. It combines a Blackwell GPU with 5th-generation Tensor Cores and a 20-core Grace Arm CPU (10× high-performance Cortex-X925 + 10× efficiency Cortex-A725 cores). Memory-wise, it’s got 128 GB LPDDR5X unified memory, split into 8 chips around the GB10 Grace GPU chip.

The CPU and GPU are connected through NVLinkTM-C2C, a Chip-to-Chip interconnect, not via PCIe slots, cables, or external connectors, and that’s faster and more energy efficient.

Note: Although PCIe 5.0 x16 is limited to ~64 GB/s for CPU-GPU transfers, DGX Spark’s unified memory architecture provides ~273 GB/s of shared memory bandwidth accessible by both CPU and GPU.

Both the CPU and GPU chips in GB10 share a coherent unified memory address space and behave like a single processor, yielding much lower latency and much higher bandwidth than PCIe. Through PCIe, the data has to flow H2C (host to chip) and C2H (chip to host) between your CPU memory space (RAM) and GPU memory space (VRAM) in a machine that has a discrete GPU, plugged into a PCIe slot on the motherboard.

Memory Bandwidth

To understand why memory bandwidth matters for DGX Spark, it helps to contrast it with a traditional discrete GPU setup.

In a conventional system, let’s say as an RTX 5090 installed in a PCIe 5.0 x16 slot - the GPU is a discrete card, separate from the CPU and system memory. Communication between the CPU and GPU is happening over PCIe 5.0, which provides roughly 64 GB/s of usable bandwidth per direction. All data movement between host memory (RAM) and device memory (VRAM) must be explicitly orchestrated by software and is not hardware-coherent.

Note: In PyTorch, when you call something like

tensor.to(”cuda:0”), you’re explicitly triggering a device transfer. This operation copies the tensor’s data from CPU system memory (RAM) into GPU device memory (VRAM) so the GPU can access and process it.If you look deeper into PyTorch’s C++ backend, you’ll find operations commonly referred to as HtoD (host-to-device) and DtoH (device-to-host). Through the cudaMemcpyAsync primitive, these allocate memory in the appropriate CPU or GPU address space and then perform explicit memory copies between them via PCIe.

DGX Spark takes a different approach. Instead of discrete CPU and GPU memory pools connected by PCIe, it uses a single, hardware-coherent unified memory system shared by both the CPU and GPU. This doesn’t need explicit HtoD and DtoH copies and allows both processors to directly access the same memory address space.

However, this design comes with a tradeoff. The unified memory pool delivers approximately ~273 GB/s of bandwidth, being a LPDDR5X system memory. This is still higher than what PCIe 5.0 provides per BUS, but is lower than the bandwidth of GPU-local memory such as GDDR7, GDDR6, or HBM.

For instance, RTX5090 has GDDR7 at ~1.5TB/s memory bandwidth of VRAM.

The DGX Spark has LPDDR5X at 273GB/s bandwidth on the unified memory.But, to consider : Spark is smaller, has really good compute capabilities, and consumes way less power than a dedicated GPU.

As a result, DGX Spark favors memory coherence and large memory size (i.e., 128GB) over raw memory throughput, which can limit performance for workloads that are heavily bandwidth-bound on the GPU.

Although the lower memory bandwidth of 273 GB/s, the Spark still yields decent inference performance for large MoE models, Image Generation Models, and some dense models, and good GPU performance for workloads that are GPU-bound, such as prompt-prefill, or model training and finetuning.

This makes Spark really well-suited for handling larger models and latency-tolerant workloads, but a slightly poorer fit for large GPU workloads that are fundamentally bandwidth-bound.

The GB10 Chip

The GB10 is a multi-die single-chip solution for high-performance Arm-based workstations. With a GPU die based on the Blackwell architecture and a CPU die built by MediaTek with 20 Arm CPU cores. Both dies are built on TSMC’s 3nm process.

Note: A CPU/GPU die is the actual, tiny piece of silicon (semiconductor) where all the transistors, cores, and processing logic for a CPU or GPU are fabricated and etched.

The Apple M4 Max, for example, has up to a 16-core CPU, a mix of up to 12 high-performance cores and 4 efficiency cores. Spark comes with 20 (10 performance, 10 efficiency).

The integrated GPU delivers up to 1 petaFLOP AI compute (FP4 sparse), and supports the optimised NVFP4 precision, a data type which only Blackwell supports.

Networking and Scalability

One major aspect that’s often overlooked in these comparisons is the networking interface built into DGX Spark. Spark includes NVIDIA ConnectX-7, a high-performance SmartNIC designed for datacenter AI and HPC workloads, not something you typically find in workstation or desktop systems.

The QSFP ports on DGX Spark support InfiniBand, for hardware-accelerated capabilities such as:

RDMA and GPUDirect RDMA for low-latency, high-throughput GPU-to-GPU and GPU-to-storage transfers, with minimal CPU involvement.

RDMA over Converged Ethernet (RoCE) for efficient multi-node communication across Ethernet-based environments.

This capability matters when you start thinking beyond single-node workloads.

For example, consider scaling LLM inference using disaggregated serving (e.g., NVIDIA Dynamo with SGLang) across multiple nodes. In this model, tokens are exchanged between multiple GPU workers selected dynamically based on their load. The system can scale workers up or down and parallelise prefill and generation phases independently, workflows that are highly sensitive to latency and interconnect performance.

With DGX Spark, this entire setup can be prototyped locally. With 2 x Sparks, one can effectively emulate a small AI cluster with 256GB of unified memory, allowing developers to validate distributed inference and system behaviour before deploying the same architecture to DGX Cloud or a larger datacenter environment.

Now, to round up the specs, the DGX Spark also comes with a fast 4 TB NVMe SSD (i.e., NVIDIA’s Founders Edition) for storage and runs a tuned Linux-based DGX OS that preloads with NVIDIA’s AI software stack for AI development from the first boot.

Rounding up the Specs

Software and Developer Experience

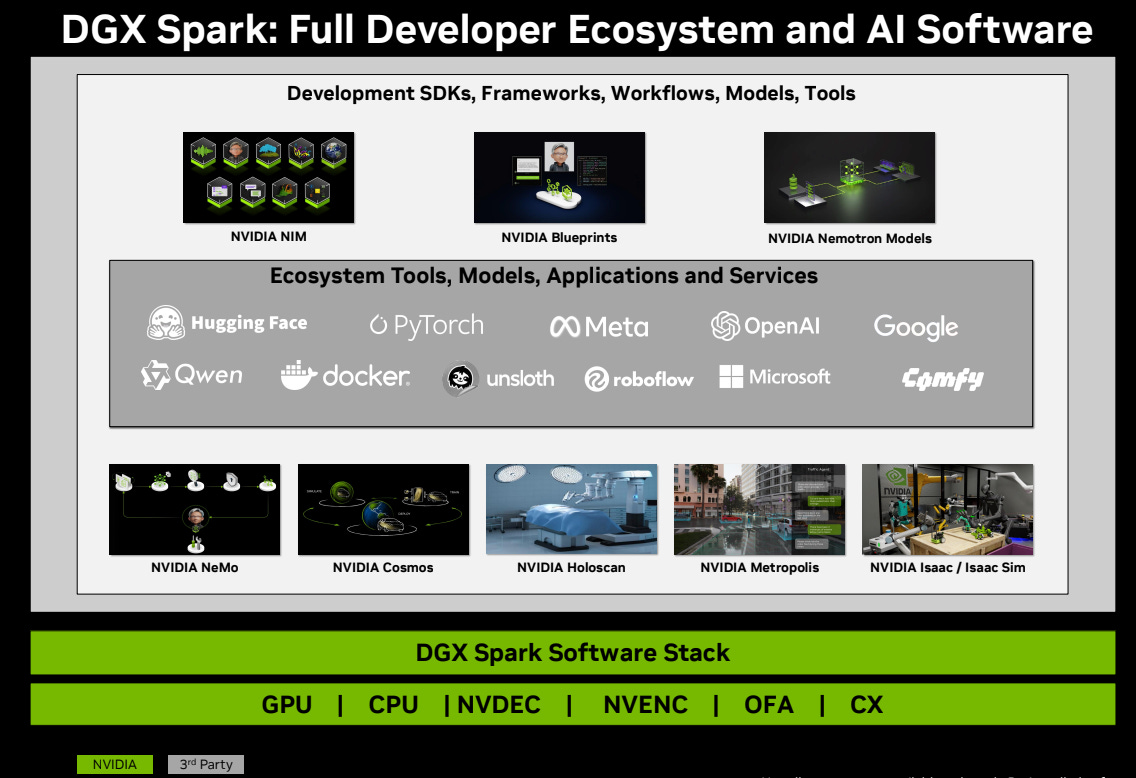

I also find one of the biggest advantages of the DGX Spark to be the software ecosystem and experience it offers to AI Developers. The Spark comes preconfigured with the full NVIDIA AI software stack through the DGX OS, so you have all the drivers, libraries, and frameworks ready to go.

This means the correct GPU drivers, CUDA toolkit, cuDNN, NCCL, TensorRT, Triton Inference Server, and key system-level optimizations are already installed and versioned as a single OS bundle. For AI developers, this removes a somewhat large amount of setup friction.

Popular tooling, such as PyTorch, JAX, Hugging Face, Llama.cpp, Ollama, LMStudio, and ComfyUI can be installed and run with minimal configuration. For developers working with LLMs, multimodal models, or image generation pipelines, this helps reduce the time-to-first-experiment.

This experience is notably different from other NVIDIA Edge AI devkits such as Jetson Nano, Orin, or AGX Thor, which rely on JetPack OS. While JetPack is well-suited for embedded and edge deployments, it is more constrained, more tightly coupled to specific hardware configurations.

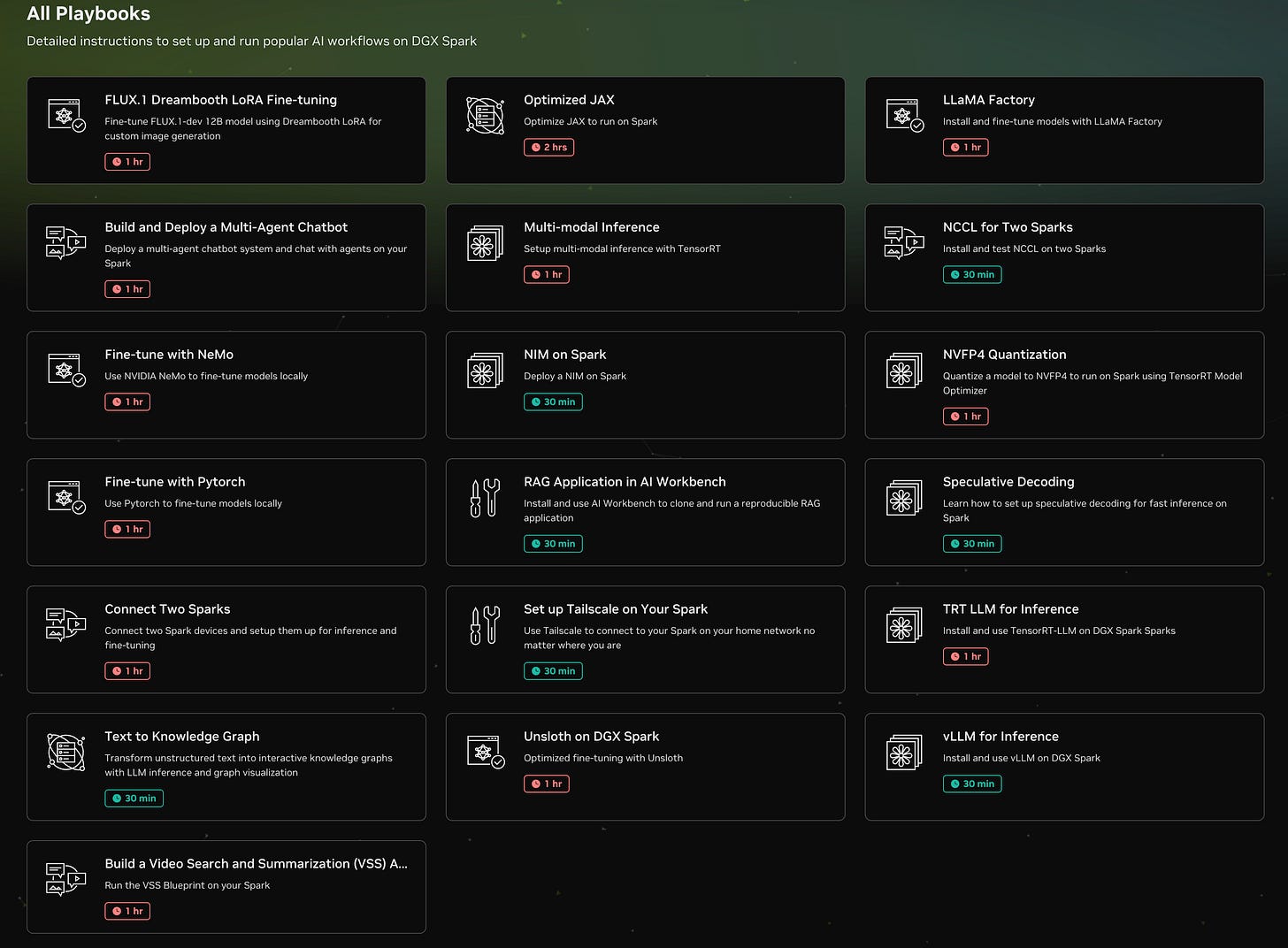

On top of the base platform, NVIDIA also provides a library of DGX Playbooks. These cover a broad range of real-world use cases, including multi-agent systems, multimodal pipelines, LLM fine-tuning, full pre-training workflows, image generation, model quantization, and production model serving.

The Benchmarks

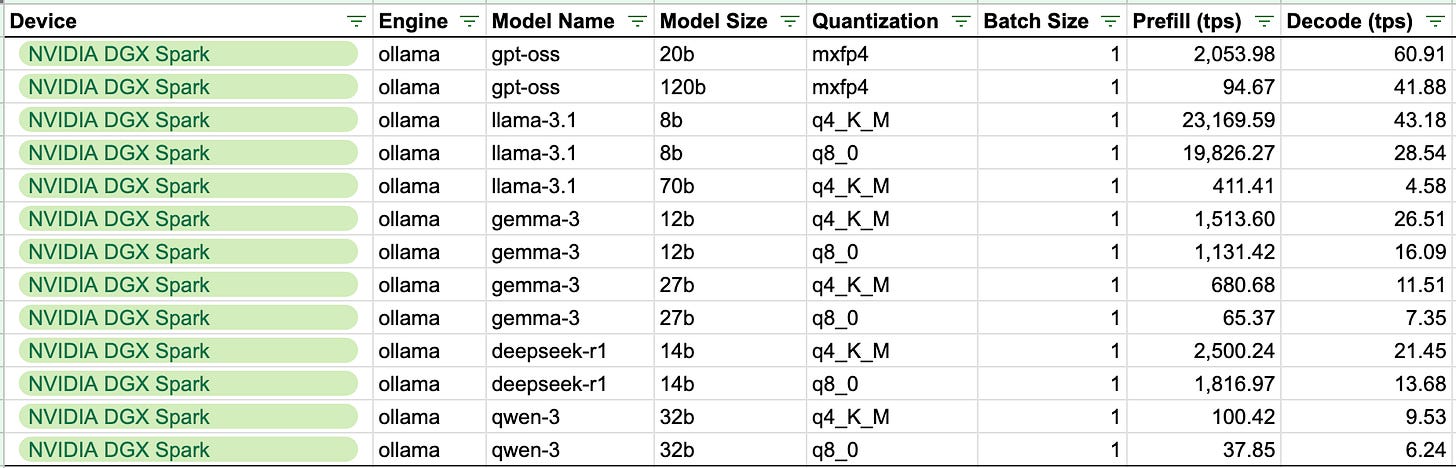

Below, I’ll present a set of DGX Spark inference benchmarks to illustrate Spark’s performance. While Spark delivers lower token decoding throughput than high-end discrete GPUs, it achieves strong prompt prefill performance thanks to the GB10 Blackwell chip and maintains decoding speeds that are practical for interactive use for most models.

Note: From a UX perspective, sustained generation speeds in the 60–70 tokens/sec range at a single session, already feel responsive. Once requests are batched, tokens/sec increase to 100 and even 200 tokens.sec.

Although I mentioned above that Spark is not really an inference box, I’m still attaching these benchmarks to outline the decent and even good performance the DGX Spark has in most use cases tested, especially in MoEs.

DGX Spark inference on LLMs ranging from Llama 3.1 8B to GPT-OSS 120B

The Spark is super fast at Prefill, which is the compute-bound phase of LLM Inference, thanks to the GB10 Superchip. But although slower at the decoding phase, which is memory-bound due to the 273GB/s that Spark has, it still yields good TPS (60 tok/s for GPT-OSS 20B, and 41 tok/s for the 120B variant).

* Plus, in these benchmarks, none of the models are quantised to NVFP4, which only Blackwell supports. Most models are in INT4, so performance is still left off the table in these cases.

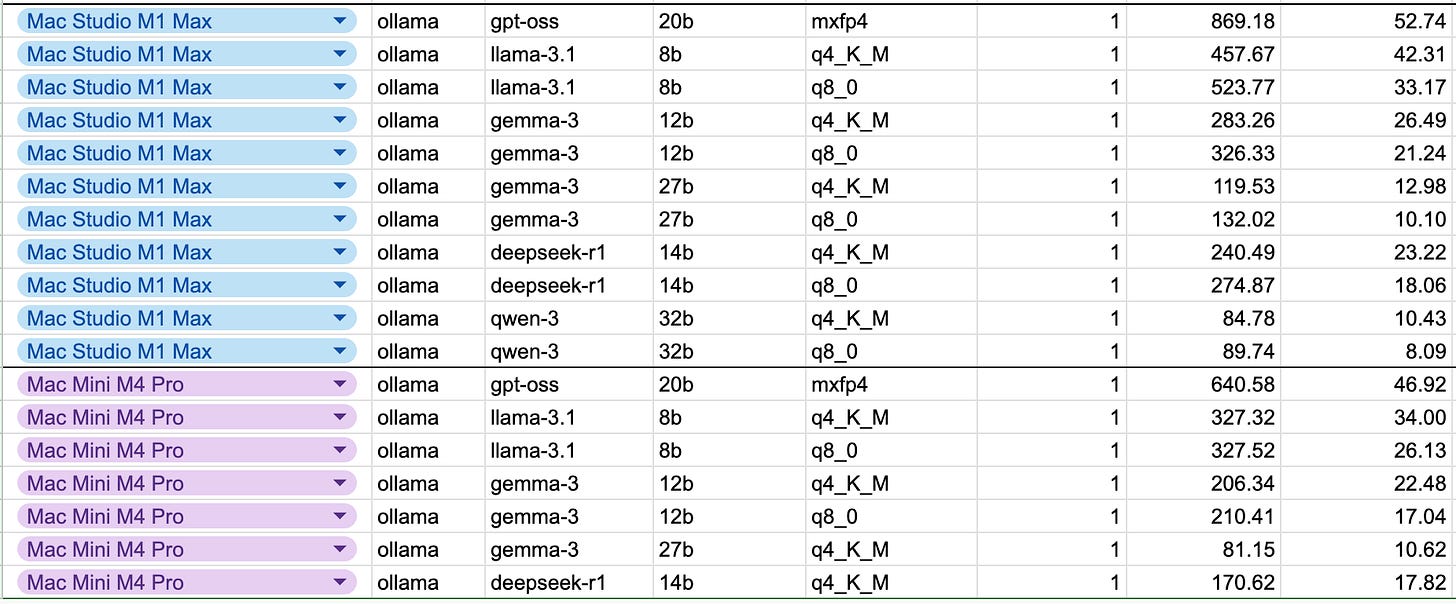

Mac Studio M1 Max and Mini M4 Pro on Llama 3.1 8B to GPT-OSS 120B

The Mac Studio M1 Max and Mini M4 Pro don’t fit larger models and don’t support the CUDA ecosystem. Results on supported models might be similar in the decoding phase, but DGX Spark outperforms in the Prefill compute-bound phase by a lot in most cases.

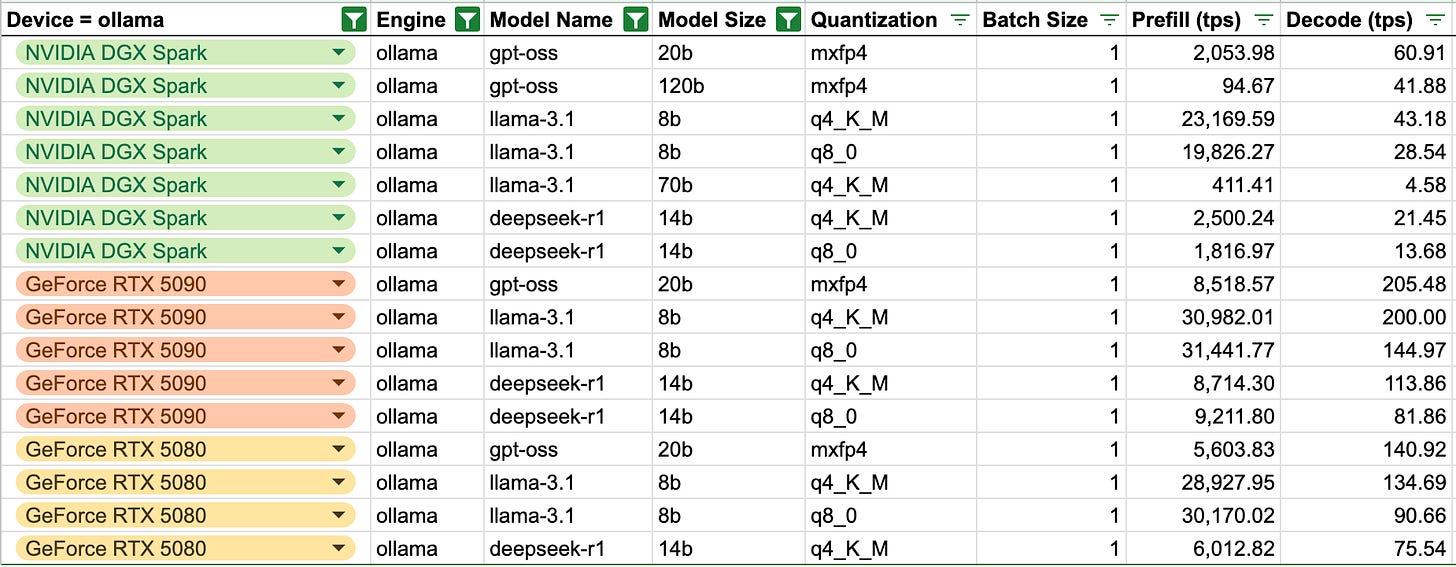

DGX Spark Inference compared to RTX5080 and 5090

The 5080/5090 come with 16GB/32GB of VRAM, which is 8/4 times lower than Spark’s 128GB of unified memory. Spark still yields good results on the prefill phase, 23.169 Tokens vs 30.982 Tokens on RTX5090 and 28.927 on RTX5080, while numbers for the generation speed are capped by the memory bandwidth, making the TG speeds on the Spark 2/3 times lower than RTX5080/5090 variants.

DGX Spark vs NVIDIA Jetson AGX Thor (VIDEO)

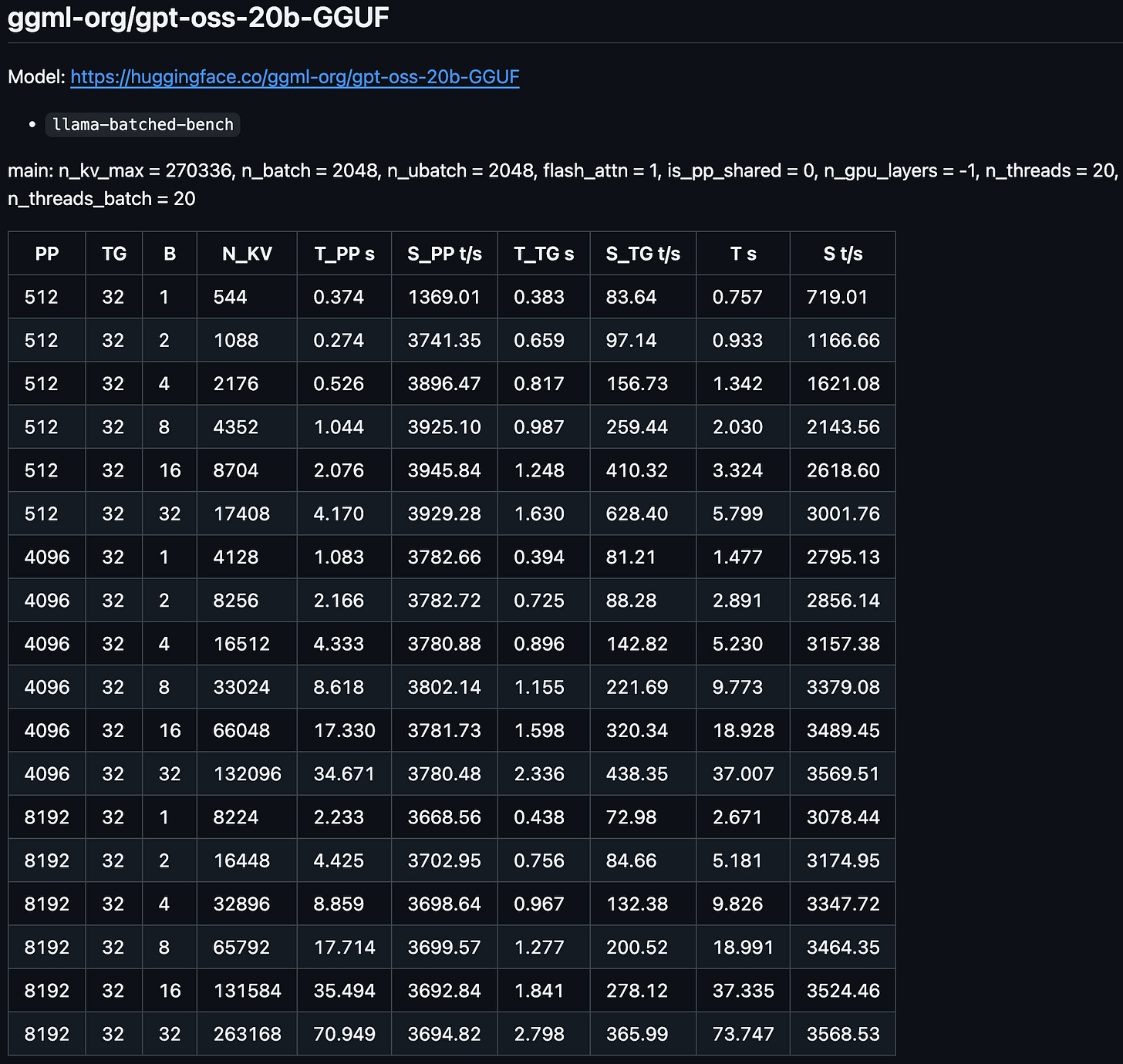

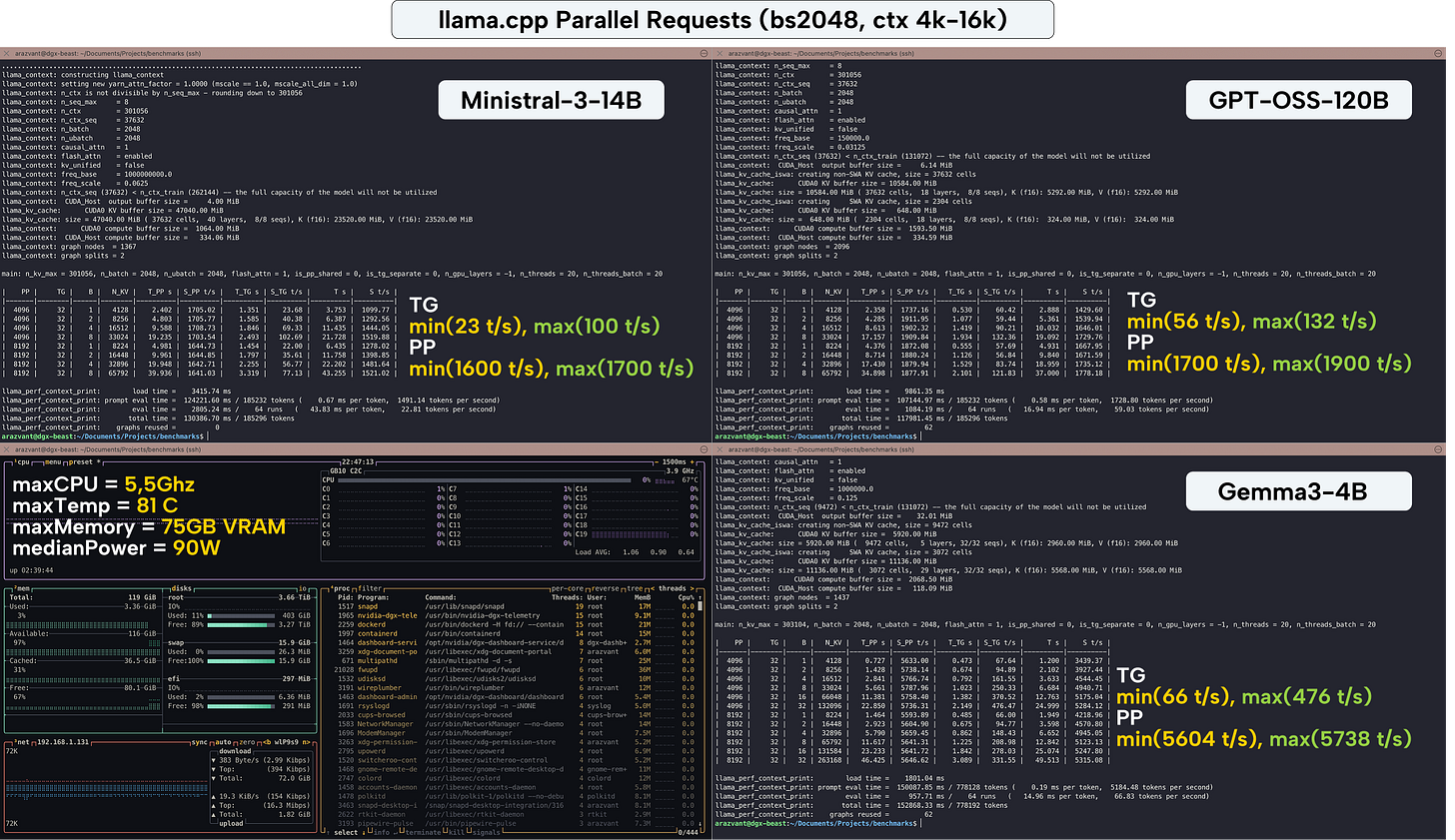

More verbose benchmarks on DGX Spark vs AGX Thor using llama.cpp

DGX Spark running Minimax-M2-230B

* Given this is a 230B model, 10-30 tok/s generation speeds are still pretty decent.Extensive Benchmarking of DGX Spark on llama.cpp

* The link above leads to a llama.cpp thread where the community is benchmarking the DGX Spark on a variety of use cases. Models include GPT-OSS-20B, Gemma3-27B, GLM4.5, etc.

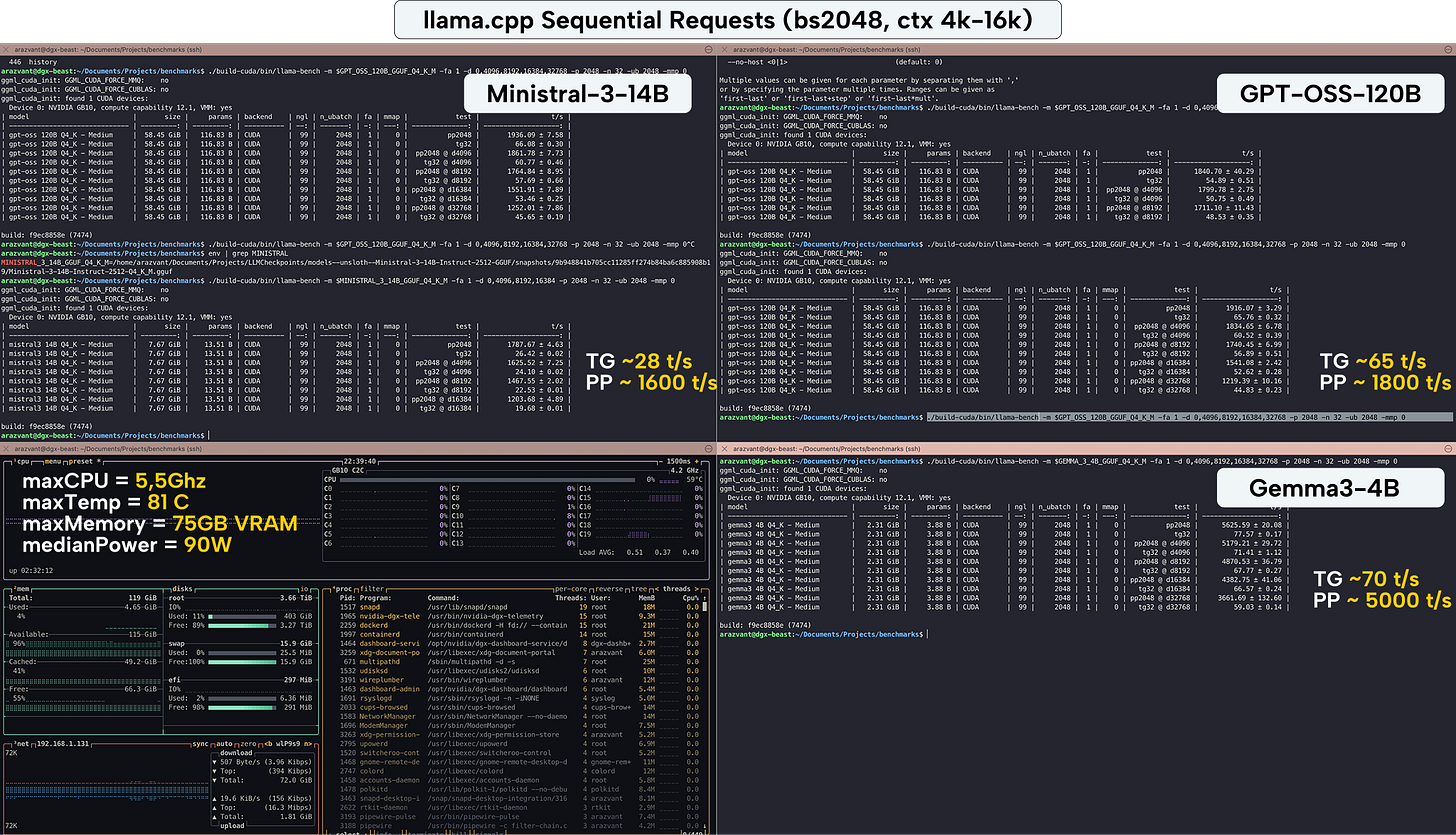

My Own Benchmarks

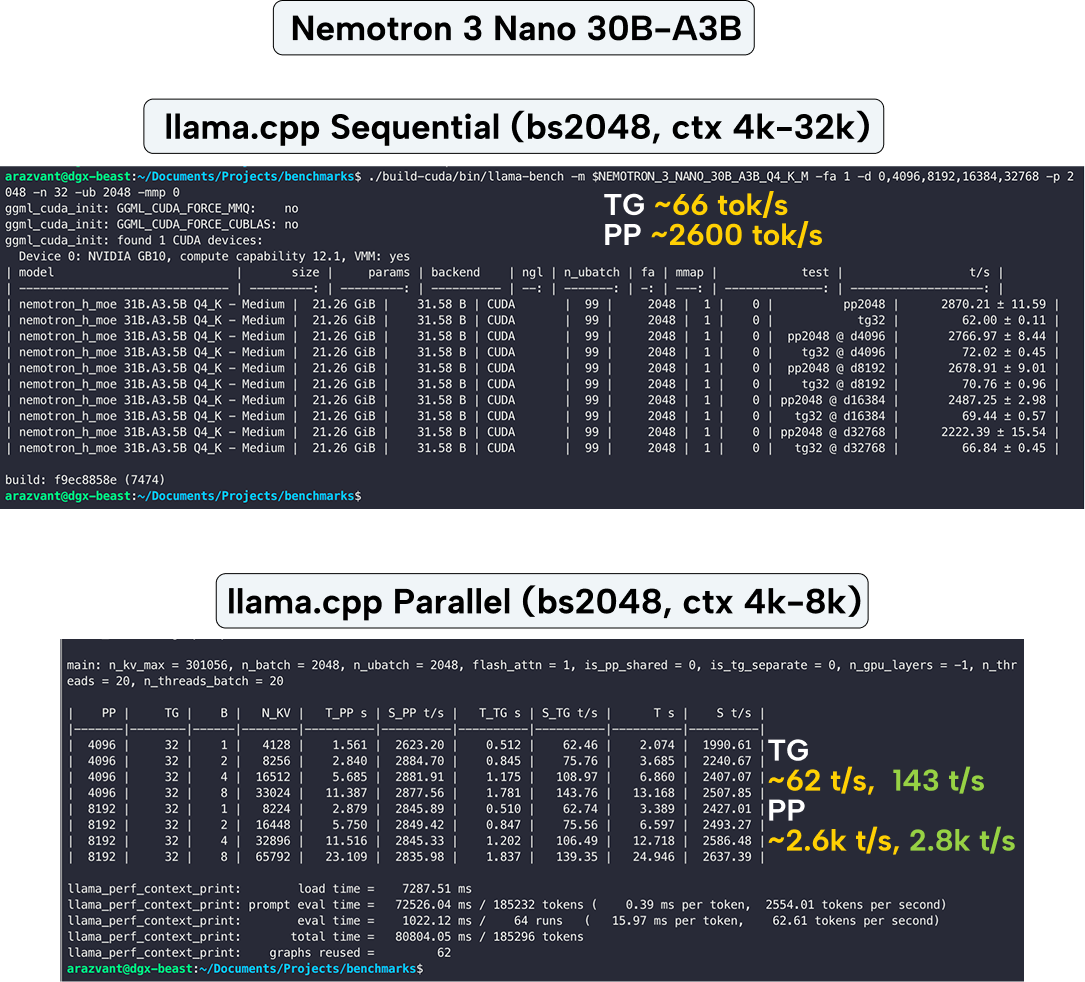

To ground my testing in realistic developer workloads, I benchmarked DGX Spark inference across four models that span small multimodal to long-context MoE models.

All tests were conducted using llama.cpp build 7474 (commit f9ec8858e), compiled with -DGGUF_CUDA=ON. I used both llama-bench and llama-batched-bench to measure performance under sequential and batched inference workloads.

The models I’ve tested:

Small multimodal (≤5B): Gemma 3 4B

Mid MoE (10–30B): Ministral-3-14B-Instruct

Large MoE (100B+): GPT-OSS-120B

Transformer Hybrid + MoE: Nemotron-Nano-3-30B-A3B

Setup Details:

The llama.cpp batching parameters I’ve used:

`-fa 1` - Enabling the FlashAttention plugin

`-ub 2048`- The prompt tokens batch size.

`-npp 4096,8192` - The npp stands for NumberPromptPrefil, and the benchmark will use 4096 tok context window, then 8192 tok context window.

`ntg 32` - This describes how many tokens to generate before measuring TokenGeneration time.

`-npl 1,2,4,8` - Concurrency/Parallel requests

`--no-mmap` - Loads the model into memory, without any cached layers.

The Results on DGX Spark

Other benchmark resources:

DGX Spark and Mac Mini for Local AI Development by Sebastian Raschka, PhD

DGX Spark Review (Mac, DGX Spark, Strix Halo) by Alex Ziskind

Availability and OEM systems

NVIDIA’s Founders Edition is available to order at $3,999 for the 4TB configuration. Alongside NVIDIA’s own unit, several GB10 desktops are arriving from the big OEMs. The core hardware will be pretty similar across all of the OEMs, with many announcements, including the Dell Pro Max, Lenovo ThinkStation PGX, Acer Veriton GN100, and ASUS Ascent GX10 having the GB10 chip.

Conclusion

The DGX Spark is best understood not as a faster GPU, but as a developer kit for building, validating, and testing large AI workloads locally.

It sits between discrete GPUs and full AI workstations within NVIDIA’s ecosystem, systems most AI developers rely on today - but packaged in a compact, desk-side form factor that fits naturally into a local development workflow.

Looking at the community benchmarks, most criticism of the DGX Spark comes from evaluating it against metrics that don’t match its intended use case. Many reviews frame it as an inference box or a replacement for high-end GPUs, but Spark was not designed to compete with large workstations purely on inference throughput.

While it doesn’t offer the memory bandwidth of high-end discrete GPUs, it still delivers practical performance on memory-bound workloads, with generation speeds that remain usable for interactive development.

More importantly, Spark is designed to align local AI development with how AI systems are actually built, whether that means working with a single large LLM, optimizing or quantizing models, fine-tuning and serving multiple smaller models, or building agentic systems that are eventually deployed at scale.

When judged on those terms, DGX Spark does exactly what it is designed to do.

Thanks NVIDIA for sending me a DGX Spark 💚

Thanks for reading Neural Bits 👋

I’ll have another update to share in the next issue, coming next week.

References

[1] NVIDIA DGX Spark. (2025). NVIDIA. https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/products/workstations/dgx-spark/

[2] Spark, D. (2019). NVIDIA DGX Spark Benchmarks. Google Docs. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1SF1u0J2vJ-ou-R_Ry1JZQ0iscOZL8UKHpdVFr85tNLU/edit?gid=0#gid=0

[3] Raschka, S. (2025, October 29). DGX Spark and Mac Mini for Local PyTorch Development. Sebastian Raschka, PhD. https://sebastianraschka.com/blog/2025/dgx-impressions.html

[4] Kennedy, P. (2025, October 14). NVIDIA DGX Spark Review: The GB10 Machine is so Freaking Cool. ServeTheHome. https://www.servethehome.com/nvidia-dgx-spark-review-the-gb10-machine-is-so-freaking-cool/2/

[5] llama.cpp/benches/dgx-spark/dgx-spark.md at master · ggml-org/llama.cpp. (2025). GitHub. https://github.com/ggml-org/llama.cpp/blob/master/benches/dgx-spark/dgx-spark.md

[6] NVIDIA DGX Spark In-Depth Review: A New Standard for Local AI Inference | LMSYS Org. (2025). Lmsys.org. https://lmsys.org/blog/2025-10-13-nvidia-dgx-spark/

[7] Mann, T. (2025, August 27). Nvidia details its itty-bitty GB10 superchip for local AI development. Theregister.com; The Register. https://www.theregister.com/2025/08/27/nvidia_blackwell_gb10/

[8] NVIDIA DGX Spark Review: The AI Appliance Bringing Datacenter Capabilities to Desktops. (2025, November 13). StorageReview.com. https://www.storagereview.com/review/nvidia-dgx-spark-review-the-ai-appliance-bringing-datacenter-capabilities-to-desktops

[9] Performance of llama.cpp on NVIDIA DGX Spark · ggml-org/llama.cpp · Discussion #16578. (2025, October 14). GitHub. https://github.com/ggml-org/llama.cpp/discussions/16578#discussioncomment-14688238

[10] NVIDIA/dgx-spark-playbooks: Collection of step-by-step playbooks for setting up AI/ML workloads on NVIDIA DGX Spark devices with Blackwell architecture. (2025). GitHub. https://github.com/NVIDIA/dgx-spark-playbooks

Regarding the DGX Spark and its focus on local AI development, this was a great overview. I'm especially reflecting on the 'large unified memory' aspect. How does this specificly improve the workflow for developing and validating models locally, particularly when considering the eventual transition to superclusters? It seems like a crucial detail for efficiency.

Nice post, learned a lot. In figure 2 it’s cm not mm.