What You Don’t See: My Engineering Process Behind Each Article

My Working Desk. How I capture ideas, sketch System Design Diagrams, Write and Build AI Projects for this newsletter.

Welcome to Neural Bits. Each week, I write about practical, production-ready AI/ML Engineering. Join over 6700+ engineers and learn to build real-world AI Systems.

How does the behind-the-scenes of writing this Newsletter look?

What you see and read in here is the final result of days, and sometimes 1-2 weeks of tinkering, sketching, building, editing, maybe recording, and finally publishing.

I spend a lot of time designing, coding, breaking things, fixing them again, and writing about what I learn. But the parts I rarely show are what happens before any code runs.

For this article, I initially thought to publish another deep dive on AI Systems. But as I didn’t feel it was complete yet, for my standards, I wanted to slow down a bit and show you the hidden side of the process.

Even though this post isn’t technical, it captures something just as important - the thinking process that drives good engineering work.

Tip: If you’re an Engineer, you’ll quickly notice that your job isn’t just to write code.

You’ll spend just as much time, if not more, reading and writing.

Explaining how systems work. Reviewing architecture documents. Writing design and tooling proposals.

Communicating clearly becomes just as valuable as building efficiently.

On that note, let me show you the behind-the-scenes of my work, building AI Systems and then writing and explaining them.

Everything happens mostly here, at my desk

Every topic I write about usually begins as a single line I drop into my Content System in Notion. It might come from a bug I’m trying to fix, a concept I want to understand, or just a random curiosity while reading.

Whenever I find something useful, a paragraph, a code snippet, a paper, or a full blog post - I save it.

Over time, I gather a lot of notes that I could filter and group into a rough plan or a more general topic that addresses a potential reader’s purpose.

On weekends, I go through those notes again and try to group them under a bigger topic I could turn into an article.

Tip: This is a habit I’ve learned from a Staff Engineer, of keeping an internal progress log in Apple Notes, Obsidian or Markdown files.

It’s simple but powerful. When you come back to a project later, you already have the full context waiting for you. Fun fact, it’s a bit like building your own RAG system, where your notes are the knowledge base, and your brain is the LLM model.

Back at it, after iterating the notes, I start to plan the structure, compose the diagrams and visuals, and jump to implementation.

A real example of the Writing Process

In January of this year, I published an article on the basics of GPU Programming for AI Engineers, one of my most-read pieces so far, with over 12k views and 110 Likes.

It came from a pile of scattered notes: CUDA, GPU architecture, custom kernels in C++ and Python, and the new Triton language from OpenAI. Around that time, I was also studying Unsloth and JIT, trying to understand how it optimizes LLM finetuning using Triton kernels.

All these notes were connected. So I grouped them, built a few examples, added visuals, and turned it into a clear and easy-to-digest guide.

Tip: Good writing is clear thinking made visible. This is an insight I’ve learned from “On Writing Well” by William Zinsser [2]

While I was also learning myself, I put my thoughts and gotchas on paper.

Why did it resonate so much?

Because AI engineers rarely build their own GPU kernels, researchers do.

But understanding how Kernels and GPUs work is a major advantage for anyone working with AI.

Thus, a hands-on introduction to how GPUs work: what CUDA is, VRAM, what a kernel looks like, and how to build one in C++, CudaPy, and Triton proved to be so helpful.

A real example of the Designing Process

Writing code for simple tutorials is easy.

You could do the initial scaffolding and share those as Jupyter Notebooks or a single Python script.

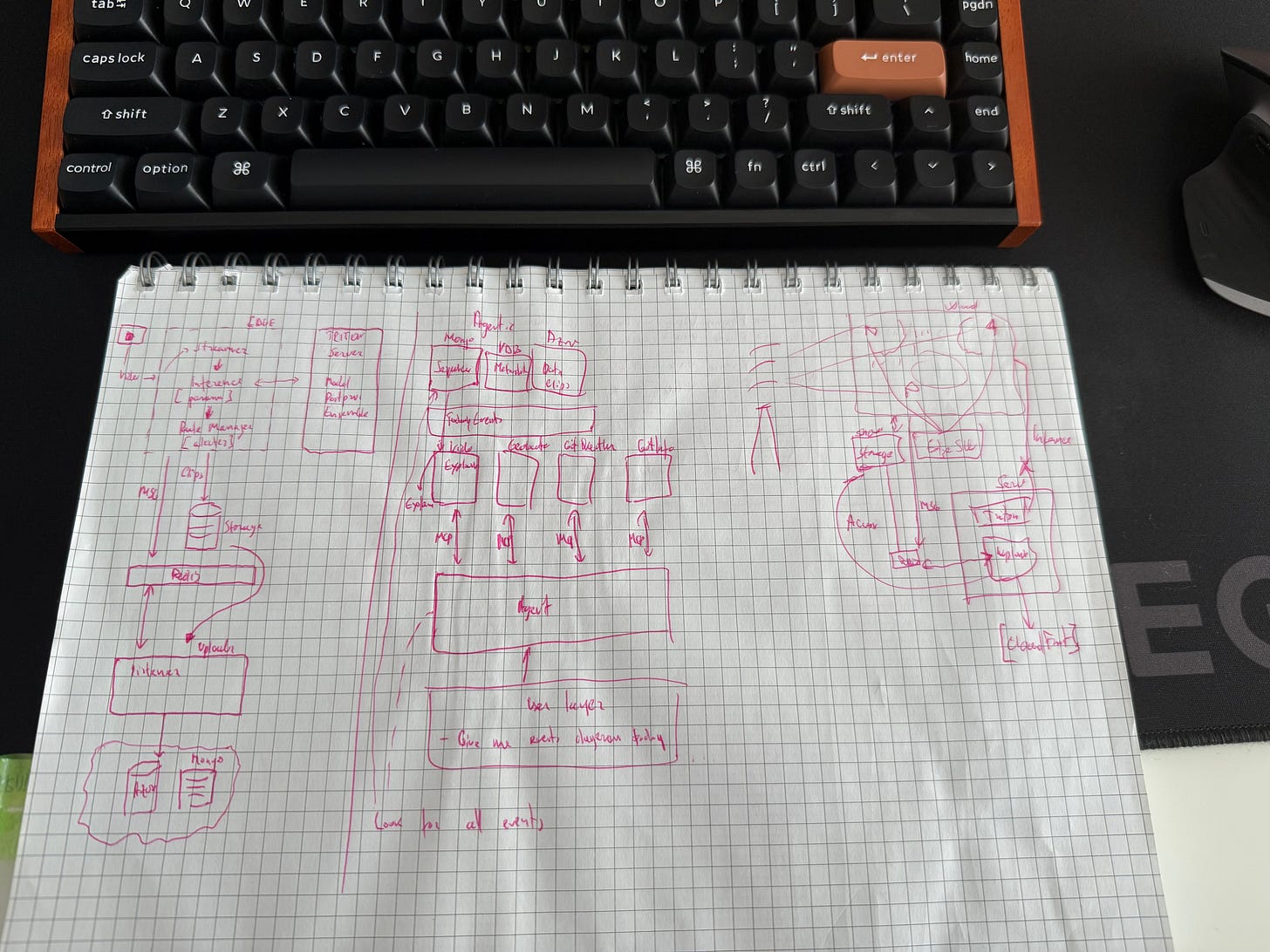

Building a bigger project with multiple components requires sketches and System Design at first.

On top of that, explaining each component and its role is super difficult if you don’t have the blueprint for that already set.

Note: Just as in any software application, re-designing components on the run adds tech depth and more engineering hours for refactoring later.

And that is something that’s often swept under the rug, prioritizing shipping new features.

Before I write any code, I usually try to nail down how everything fits together. At first, pen and paper, most of the time nothing fancy - just quick diagrams to help me see how the pieces fit together.

However, using quick sketches doesn’t cover everything. I had multiple instances where something I thought about initially doesn’t scale, has a major flaw, or simply doesn’t work.

Tip: Chip Huyen’s book ‘Designing Machine Learning Systems’ [5] contains really good advice on how to properly design ML Systems.

There were times when I had a flashing idea of how to add a component or remove another one entirely from my initial plan. In my case, these ideas stay latent in the back of my mind and come up at unusual times.

For example, one instance I remember was when I was reading Atomic Habits [1] by James Clear, relaxing on the couch, and suddenly, I got the idea of how I could fix the Storage structure component in one of my projects.

Totally unexpected, no connection between the book I was reading and the initial diagram sketch I’ve done a few weeks prior.

Usually, those ideas don’t stay in your mind for too long, so you've got to act fast.

In that case, a system design diagram can turn into something like this, which is messier, but closer to the final working version.

Just like in real engineering work, only after a system is reviewed and iterated over can you get to a plan to start implementing and turning sketches into real working components.

Before reaching this stage, there’s a lot of invisible work, revisiting assumptions, balancing trade-offs, and running thought experiments before any code exists.

Note: In real AI/ML or SWE projects, you won’t do this alone, but as part of a team. Understanding how this process works keeps everyone on the same page.

That’s the heart of engineering thinking. The cheapest bugs to fix are the ones you catch in your design, not your deployment, which is more important for AI/ML projects than standard software and SDLC (Software Development Lifecycle).

The big plot twist

In software engineering, we can design, build, test, and deploy in a fairly linear way. All the tooling and components are established, resilient, and tested in production.

In AI/ML, the cycle loops back on itself (MLOps). Standardization is still a work in progress.

We’re at the phase where we have a lot of tools and techniques, but fewer standardizations and production-tested methods.

That’s why designing AI Systems is, at times, far more complex than standard applications.

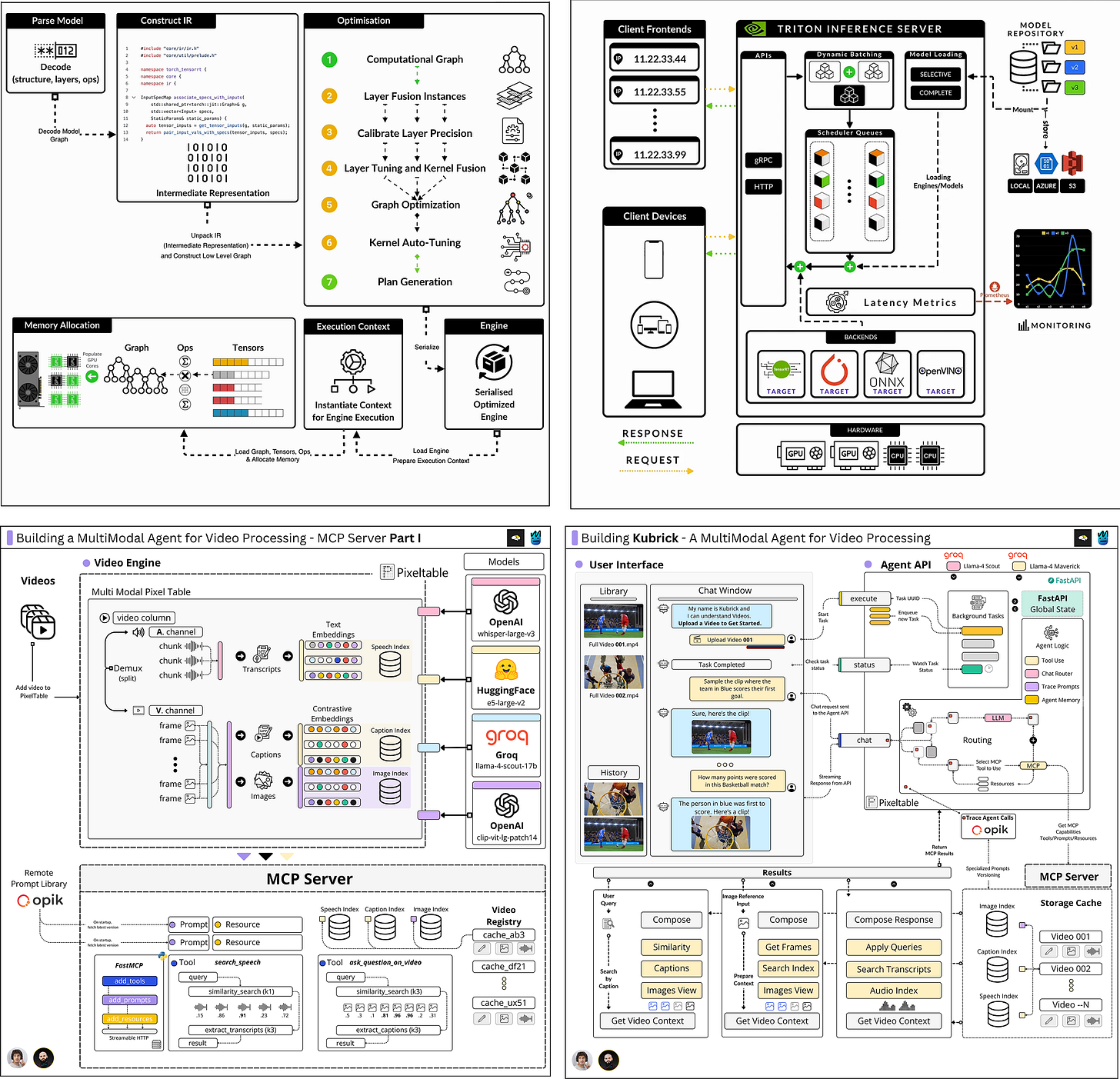

A real example of the Building Process

Once the system design feels solid enough, or at least has fewer gaps, I start building.

Note: As an example, I’ll be using a recent AI Agent based project I’ve worked on.

I begin by setting up the foundations, mostly starting with a blank, single Python script that will get me something working as fast as possible. At this stage, I usually avoid optimizations or abstractions - just focusing on getting something to run end-to-end, pure Python.

I don’t finetune or optimize models yet, version or track my prompts, add in databases, or throw in MCP and Agents.

If I need multiple customizable prompts, for example, I’ll extract them from Python and save them alongside code, in Markdown.

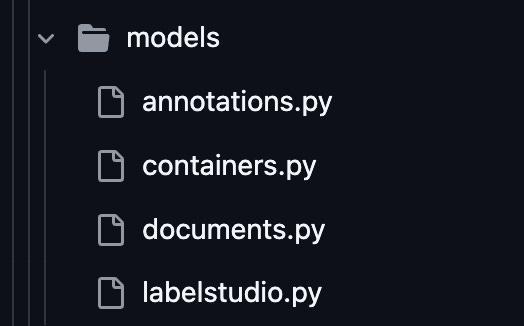

Next, I split the project into components to separate concerns and add strict models that will define the workflow, since I already have the system design diagrams in place. For example, I can define a collection of reusable Pydantic models that act as contracts between components.

These data models help me validate input/output, keep types consistent, and debug issues in isolation.

Some of the next steps would be to build the minimal functionality on each component, as defined in the System diagram, and aim to test them in integration.

As I’m reaching the email length limit, I’ll skip over the details of those steps for now, but this is usually where structuring the project is something I’ll consider.

As the codebase grows, I want it to stay easy to navigate and evolve, without different components becoming tangled in ways they shouldn’t.

The exact setup can vary.

I usually follow the Clean Architecture software pattern, which I’m most familiar with.

A nice template for your AI projects, that follows the Clean Architecture pattern, is this one by Miguel Otero Pedrido (from The Neural Maze [4]), which I recommend if you want to start fresh or already have an AI project that became cluttered and you want to bring a scalable and readable structure to it.

Be it Clean Architecture [3], Clean Architecture with DDD, or Vertical Slice, the key idea remains the same: keep boundaries clear and logic isolated.

Ending Notes

Every article, project, or idea starts the same way - rough notes and bad sketches.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned through all of this, it’s that clarity comes from iteration. The more you think, design, and rebuild, the simpler things become.

That’s when everything finally clicks.

I hope this gave you a few insights into how to think about your own engineering process.

Thank you for reading. See you next week!

References

[1] Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. (2025, June 24). James Clear. https://jamesclear.com/atomic-habits

[2] Amazon.com: On Writing Well, Zinsser, William: https://www.amazon.com/Writing-Well-Classic-Guide-Nonfiction/dp/0060891548

[3] Clean Architecture: A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design (Robert C. Martin Series) https://www.amazon.com/Clean-Architecture-Craftsmans-Software-Structure/dp/0134494164

[4] Pedrido, M. O. (2025, August 6). The Neural Maze. Substack.com; The Neural Maze. https://theneuralmaze.substack.com/

[5] Amazon.com: Designing Machine Learning Systems: An Iterative Process for Production-Ready Applications: 9781098107963: Huyen, Chip: Books. (2025). Amazon.com. https://www.amazon.com/Designing-Machine-Learning-Systems-Production-Ready/dp/1098107969

Great article man! LOVE your working setup ♥️